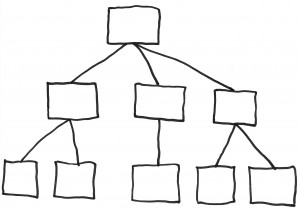

Probably my favourite tool in the arsenal of analyst techniques has to be decomposition. Whether it’s functional or process decomposition there is nothing like it for arranging problems into the big picture. Then breaking that picture down into its component parts so that you can start to make sense of it.

Probably my favourite tool in the arsenal of analyst techniques has to be decomposition. Whether it’s functional or process decomposition there is nothing like it for arranging problems into the big picture. Then breaking that picture down into its component parts so that you can start to make sense of it.

And yet hierarchy, in recent years, has got a pretty bad reputation. As Stanford professor Bob Sutton wrote this weekend in this LinkedIn article. He was brought up to believe that hierarchy was bad and led to inefficiency, yet research for his new book showed that hierarchy is unavoidable.

Hierarchy is nature’s gift to us in helping us understand the World around us. Citing research by his colleagues Deb Gruenfeld and Lara Tiedens he describes how hierarchy is found in every single group of animals found in nature. To quote Gruenfeld and Tiedens directly:

When scholars attempt to find an organization that is not characterized by hierarchy, they cannot.

Hierarchy structures the relationships between people and things into parent, child and peer relationships. This makes it easier for us to remember those relationships, it provides an organising principle that is standardised across everything. We simply have to know how hierarchy works in order to understand something that is new to us.

This is what makes decomposition so powerful. It comes naturally to us human beings so is not really something that needs much in the way of education. When we apply it, it’s often to an area that seems chaotic and complex. By decomposing we overlay a hierarchy that allows us to understand what was previously incomprehensible. It allows us to break problems down into component parts in order to tackle them effectively and even start to predict what will happen when we make changes.

It doesn’t just aid understanding, it also helps us to remember. Instead of having to remember every single discreet component of an organisation you simply need to remember a small subset. You can then use this along with the hierarchical organising principle and you will be able to fairly accurately calculate the missing pieces.

This is what makes decomposition one of the first things I do when introduced to a new problem.

An extended version of this article is available at the-skore.com.

All Things D

All Things D ARS Technica

ARS Technica Engadget

Engadget GigaOM

GigaOM Mashable

Mashable TechCrunch

TechCrunch The Verge

The Verge Venture Beat

Venture Beat Wired

Wired Chris Brogan

Chris Brogan Brian Solis

Brian Solis Chris Dixon

Chris Dixon Clay Shirky Blog

Clay Shirky Blog HBR Blog

HBR Blog IT Redux

IT Redux Jeremiah Owyang

Jeremiah Owyang Radar O'Reilly

Radar O'Reilly Seth Godin Blog

Seth Godin Blog SocialMedia Today

SocialMedia Today Solve for Interesting

Solve for Interesting The TIBCO Blog

The TIBCO Blog Lifehacker

Lifehacker

If it is the System or Process to be designed that you are modeling, then you are NOT decomposing the problem. You are “hypothesizing the system or process to be designed” and “analyzing the parts hypothesized”.

A NEW SYSTEM that is yet to be developed CANNOT be decomposed since there is NOTHING to start with!

This is an interesting idea…that hierarchy is necessary (because decomposition requires hierarchy to exist). Zappos is famously launching a holacratic workplace where there are no job titles, no managers and no hierarchy. But if that’s how we comprehend things, and decomposition is required to understand, how does a company function without people hierarchies?

Putcha, but even a new system has to have a design, which includes components that function together to create a larger value (a hierarchy, no?). I would think a new system has only a design hierarchy and doesn’t have a physical one until it is created.

Jeanne, the Zappos stories are odd, to me. I don’t really understand how a company can operate as a holacracy…maybe it’s just too big for my brain.

Thanks for the comment Putcha.

It’s true that when designing a new system (I assume by system you mean software) we are not decomposing the problem. I guess we are designing a ‘hypothetical’ system by laying out a high level design then decomposing the components.

I would argue that, while the system itself has not been built, we overwhelming use recognised common patterns to determine which components we will use and in what order. We decompose these ‘known’ patterns to a point where the pattern diverges from the standard. Even then we would continue to breakdown the designs so that we can assign different components to different members of the team to develop.

Hi Jeanne, it’s worth reading the referenced article by Bob Sutton regarding the Zappos experiment. It’s not without precedent and Sutton gives Google as an example where it had been tried, and failed, in the past. Valve is a good example of a successful flat(ish) organisation. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Valve_Corporation#Organizational_structure

Cris and Graig:

When the system to be developed is NEW you only have a black box for the SuD, Which has NO components, NO structure, NO hierarchy NOTHING.

So, “decomposition” or “hierarchy” CANNOT BE the “first thoughts” about the black box SuD.

The “first thought” about the black box SuD can only be a hypothetical SuD with composition with some hypothetical

Sorry that got posted accidentally…..

My point is that we actually DO NOT know exactly how a NEW, really NEW SuD is to be conceived before it is described.

So, applying any of the analysis techniques can NEVER be relevant for “true creation or design”.

You may take a look at

I refer to Ackoff’s video in which he said this http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IJxWoZJAD8k. See all the “3 parts.” This is very profound and it operates whether one knows it or not. I am interested in applying it to software design more rigorously. Feel free to reach me at [email protected]

You may search for and read:

Pinterest’s Founding Designer Shares His Dead-Simple Design Philosophy

WRITTEN BY: Sahil Lavingia

Best wishes,

Interesting viewpoints, but I believe we make a mistake when we define organisations as just the sum of systems and processes. I would agree that in analysing systems and processes, the hierarchy is a useful tool to understand and structure these aspects of an organisation. The organisation of people, and how they interact, does not necessarily have to reflect those hierarchies. In fact they could leverage the inherent qualities of process and systems to make workers and teams more independent and less supervised and controlled. The holacracy, as advocated by the likes of Sutton and to a degree also by pioneers like Doug Kirkpatrick (see his TED talk about the self-managed organisation http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ej4n3w4kMa4) more concerned with how people organise themselves using the processes and systems in a radically different context. Hierarchies are our comfort zone, but we may miss an opportunity to exploit our newly networked organisations, when we stick to the old ‘command & control’ paradigm.

Excellent comment Rob and agree that the ‘official’ organisational structures and processes don’t tell you the real structures of influence within an organisation. Whenever I work with a new organisation I enjoy trying to work out who is ‘really’ in charge and who is guiding who.

What I have found is that even in a flatish organisation there is a hierarchy of influence that is typically undocumented but largely accepted and perpetuated by those in it.

Very true, Craig! There are flattish organisations, but perhaps only a handful that are seen to be ‘egalitarian’ in the way power and influence is exerted and distributed. It is very difficult to grow a company with a self-managed workforce when markets (investors, stakeholders, governments, educational systems) place traditional demands on an organisation. It takes extraordinary leadership and a strong culture to see that one through. I like Doug Kirkpatrick’s Morning Star case study and it stands out as an example that has stood the test of time, but there aren’t many success stories we can draw from at the moment.